What they didn't teach me at the business school about SBP's Magic Money Tree

SBP creates money out of thin air, at zero cost, with limited constraints while earning risk-free interest income on that money.

Some housekeeping. This post is a bit long for email so it may get truncated by the time you reach the end. You may want to read it on the website if that is the case.

I wanted to do this post for a long time. The trigger of this post, unsurprisingly, had been the WhatsApp leaked SBP amendment act. It took me some time to collect my disparate thoughts in a single post and to finally think through my arguments.

The discussion in op-eds and influencer groups with respect to the amended act has revolved around SBP's independence whereas I believe the real discussion needs to happen on SBP's mandate and SBP's quasi-fiscal activities (QFAs). I have covered the misguided focus on price stability mandate in my posts previously. In this post, I will discuss SBP refinancing which, if you are steeped in IMF thinking, is a form of QFA.

Refinancing activities are the magic money trees of SBP. They are subsidies where SBP creates money out of thin air, at zero cost, with limited constraints while earning risk-free interest income on that money.

This post has some overlap with what I have discussed in my earlier posts. I have divided it into sections so that you can skip over my arguments that you are familiar with. Section 1 and 2 set the stage. The first section discusses the clauses in the revised SBP Act with respect to quasi-finance activities. Section 2 talks about how money is created in the modern economy by commercial banks and the constraints they face. Section 3 takes it one step forward and shows how central banks don't face the same constraints as commercial banks when it comes to creating money and gives examples from Pakistani banking of how SBP can create an unlimited amount of money through refinancing. Section 4 talks about the different accounting treatment subsidies receive based on whether they are classified as fiscal activities or quasi-fiscal activities. Section 5 is a brief overview of the politics and optics of QFAs. in light of the earlier discussion, Section 6 tries to drive home the point that the new SBP Act is found wanting. Finally, the conclusion section just summarizes the post in a few bullet points.

Section 1 - Background: QFAs and Section 20

You can skip this section if you have read my previous posts on SBP Act.

SBP undertakes refinancing activities under Section 17 of the SBP Act 1956. Export Refinancing (ERF) is provided under Section 17(2)(a) and long-term facilities such as TERF and RFCC under Section 17(2)(d).

Section 17 (2) of SBP Act 1956

(a) The purchase, sale and rediscount of bills of exchange and promissory notes drawn on and payable in Pakistan and arising out of bona fide commercial or trade transactions bearing two or more good signatures one of which shall be that of a scheduled bank, and maturing within one hundred and eighty days from the date of such purchase or rediscount, exclusive of days of grace;

d) The purchase, sale and rediscount of bills of exchange and promissory notes drawn and payable in Pakistan and bearing two or more good signatures one of which shall be that of scheduled bank, or any corporation approved by the Federal Government and having as one of its objects the making of loans and advances in cash or kind, drawn and issued for financing the development of agriculture, or of agricultural or animal produce or the needs of industry, having maturities not exceeding twelve and a half years from the date of such purchase of rediscount;

As per Section 20 of the revised SBP Amendment Act, SBP will not undertake any quasi-fiscal activities and development finance activities

Section 20. Business which the bank may not transact:

Undertake any quasi-fiscal operations or development finance activities.

And in Section 2 (definition)

(7)(q) "development finance activities" means any activity undertaken to promote any priority sector such as agriculture, SMEs, housing and other sectors.

The act does not define QFAs (a major omission) but as the language is reportedly by IMF trained management, let's see what is the understanding of QFAs at IMF:

Quasi-fiscal activities are any activities undertaken by state-owned banks and enterprises, and sometimes by private sector companies at the direction of the government, where the prices charged are less than usual or less than the “market rate.” Examples include subsidized bank loans provided by the central bank or other government-owned banks, and noncommercial public services provided by state-owned enterprises.1

The International Monetary Fund has provided the following outline of different types of quasi-fiscal activities, to which some examples are added to clarify how they might work.2 Operations related to the financial system

Subsidized lending, where state-owned banks provide subsidized loans to state enterprises or the private sector.

Under-remunerated reserve requirements, where banks are required to hold reserves on which they gain a reduced profit from that which they could earn by investing the funds.

Credit ceilings, where banks are subject to a limit on the amount of credit which they are allowed to issue.

The refinancing facilities provided by SBP are a form of subsidized lending. Thus, on one hand, SBP Act defines the mechanism in Section 17 under which SBP can undertake refinancing activities (a QFA), and on the other hand, refinancing activity appears to prohibited under Section 20. I had quipped earlier:

what section 17 giveth, section 20 taketh away

Section 2 - How banks create money and the constraints

This section is based on an excellent 2014 Bank of England paper Money creation in the modern economy which talks about how commercial banks create money. I will focus on the relevant parts of the paper. Commercial banks are special institutions that can create money by just making loans. From the paper:

In the modern economy, most money takes the form of bank deposits. But how the bank deposits are created is often misunderstood: the principal way is through commercial banks making loans. Whenever a bank makes a loan, it simulataneously creates a matching deposit in the borrower's bank account, thereby creating new money.

The reality of how money is created today differs from the description found in some economics textbooks:

Rather than banks receiving deposits when household save and then lending them out, bank lending creates deposits.

In normal times, the central bank does not fix the amount of money in circulation, nor is the central bank money 'multiplied up' into more loans and deposits.

But commercial banks cannot continue to create money indefinitely as they face certain constraints such as deposit/reserve/funding constraint, liquidity risk, credit risk, and prudential regulations.

Funding constraint and spread

That is because banks have to be able to lend profitably in a competitive market, and ensure that they adequately manage the risks associated with making loans. Banks receive interest payments on their assets, such as loans, but they also generally have to pay interest on their liabilities, such as savings accounts. A bank’s business model relies on receiving a higher interest rate on the loans (or other assets) than the rate it pays out on its deposits (or other liabilities). Interest rates on both banks’ assets and liabilities depend on the policy rate set by the central bank, which acts as the ultimate constraint on money creation. The commercial bank uses the difference, or spread, between the expected return on their assets and liabilities to cover its operating costs and to make profits. In order to make extra loans, an individual bank will typically have to lower its loan rates relative to its competitors to induce households and companies to borrow more. And once it has made the loan it may well ‘lose’ the deposits it has created to those competing banks. Both of these factors affect the profitability of making a loan for an individual bank and influence how much borrowing takes place. For example, suppose an individual bank lowers the rate it charges on its loans, and that attracts a household to take out a mortgage to buy a house. The moment the mortgage loan is made, the household’s account is credited with new deposits. And once they purchase the house, they pass their new deposits on to the house seller....It is more likely than not that the seller’s account will be with a different bank to the buyer’s. So when the transaction takes place, the new deposits will be transferred to the seller’s bank. The buyer’s bank would then have fewer deposits than assets. In the first instance, the buyer’s bank settles with the seller’s bank by transferring reserves [accounts maintained at central bank]. But that would leave the buyer’s bank with fewer reserves and more loans relative to its deposits than before. This is likely to be problematic for the bank since it would increase the risk that it would not be able to meet all of its likely outflows. And, in practice, banks make many such loans every day. So if a given bank financed all of its new loans in this way, it would soon run out of reserves. Banks therefore try to attract or retain additional liabilities to accompany their new loans. In practice other banks would also be making new loans and creating new deposits, so one way they can do this is to try and attract some of those newly created deposits. In a competitive banking sector, that may involve increasing the rate they offer to households on their savings accounts. By attracting new deposits, the bank can increase its lending without running down its reserves. Alternatively, a bank can borrow from other banks or attract other forms of liabilities, at least temporarily. But whether through deposits or other liabilities, the bank would need to make sure it was attracting and retaining some kind of funds in order to keep expanding lending. And the cost of that needs to be measured against the interest the bank expects to earn on the loans it is making, which in turn depends on the level of Bank Rate set by the Bank of England. For example, if a bank continued to attract new borrowers and increase lending by reducing mortgage rates, and sought to attract new deposits by increasing the rates it was paying on its customers’ deposits, it might soon find it unprofitable to keep expanding its lending. Competition for loans and deposits, and the desire to make a profit, therefore limit money creation by banks.

Liquidity Risk

Banks also need to manage the risks associated with making new loans. One way in which they do this is by making sure that they attract relatively stable deposits to match their new loans, that is, deposits that are unlikely or unable to be withdrawn in large amounts. This can act as an additional limit to how much banks can lend. For example, if all of the deposits that a bank held were in the form of instant access accounts, such as current accounts, then the bank might run the risk of lots of these deposits being withdrawn in a short period of time. Because banks tend to lend for periods of many months or years, the bank may not be able to repay all of those deposits — it would face a great deal of liquidity risk. In order to reduce liquidity risk, banks try to make sure that some of their deposits are fixed for a certain period of time, or term. Consumers are likely to require compensation for the inconvenience of holding longer-term deposits, however, so these are likely to be more costly for banks, limiting the amount of lending banks wish to do.

Credit Risk

Individual banks’ lending is also limited by considerations of credit risk. This is the risk to the bank of lending to borrowers who turn out to be unable to repay their loans. In part, banks can guard against credit risk by having sufficient capital to absorb any unexpected losses on their loans. But since loans will always involve some risk to banks of incurring losses, the cost of these losses will be taken into account when pricing loans. When a bank makes a loan, the interest rate it charges will typically include compensation for the average level of credit losses the bank expects to suffer. The size of this component of the interest rate will be larger when banks estimate that they will suffer higher losses, for example when lending to mortgagors with a high loan to value ratio. As banks expand lending, their average expected loss per loan is likely to increase, making those loans less profitable. This further limits the amount of lending banks can profitably do, and the money they can therefore create.

Prudential Regulations

Market forces do not always lead individual banks to sufficiently protect themselves against liquidity and credit risks. Because of this, prudential regulation aims to ensure that banks do not take excessive risks when making new loans, including via requirements for banks’ capital and liquidity positions. These requirements can therefore act as an additional brake on how much money commercial banks create by lending

The funding constraint implies that as the bank makes more loans, it may need to attract deposits. The bank can do this by offering a higher rate of returns on deposits. This will increase the cost of funds for the commercial banks. Therefore, to make additional loans, the commercial bank will have to increase the interest rate on the loan if it wants to maintain the spread. The commercial bank faces the deposit constraint because it is not a monopoly and it has to compete with other commercial banks in attracting the deposits. If there was only one bank in the economy, if the commercial bank was a monopoly, and all the customers maintained their deposit accounts with this bank, then this commercial bank may not face a deposit/funding constraint.

It turns out there is such a bank in the economy that is a monopoly i.e. central bank.

Section 3 - Central bank money creation

Unlike commercial banking where borrowers may maintain accounts at different banks, there is usually one central bank and all commercial banks have to maintain accounts at this bank. As a banker of last resort, the central bank is a monopoly. Thus the central bank can create unlimited deposits without being limited by the funding constraint. In the case of commercial banks, funding constraint implied that the commercial bank has to pay higher interest to attract funds from customers i.e. funding constraint leads to higher funding cost. No such constraint for a central bank means that the central banks can create money at zero cost indefinitely.

Similar to commercial banks, the central bank creates money by crediting the accounts of the commercial banks (called reserve accounts) maintained at the central bank. In double-entry accounting, using the example of export refinance (ERF), the central bank adds the loan balance to the account of the commercial bank on the asset side and increases the deposit/reserve of the commercial bank on the liability side of the central bank's balance sheet.

Below is a simple T-account depiction of how SBP will create money/deposit/loan of Rs.100 when carrying out export refinance.

On the asset side, SBP will create a loan of Rs.100 to the commercial bank while on the liability side it will credit the deposit/reserve account of the commercial bank by Rs.100.

On the books of the commercial banks, the loan from SBP is reflected as borrowing from SBP on the liability side and it replicated by export refinance loan to the exporter on the asset side.

If the exporter writes a cheque to its supplier who maintains an account at UBL, HBL can just transfer the newly credited SBP reserves to the account maintained by UBL at SBP. Thus refinancing from SBP eliminates the funding constraint on HBL.

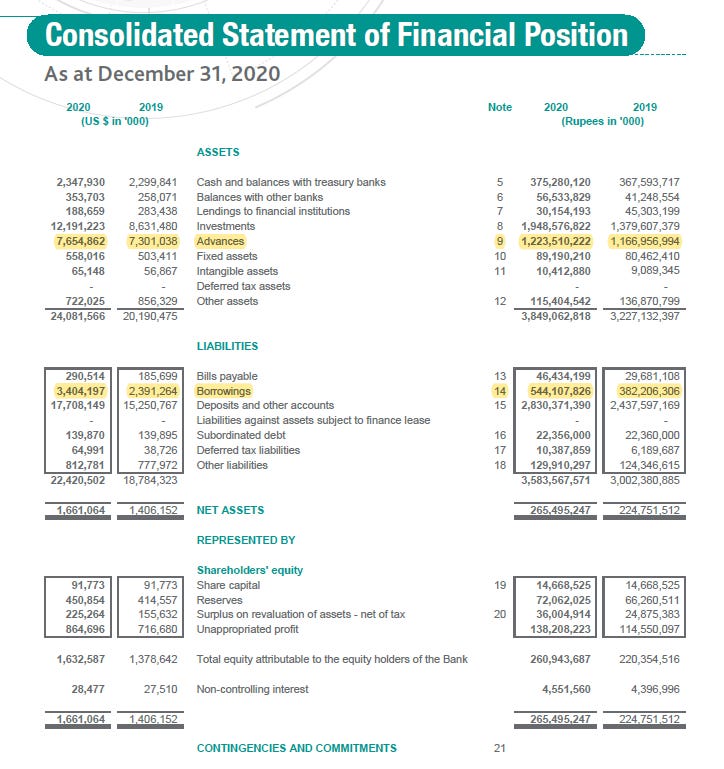

Example from SBP and HBL balance sheet

Below I have highlighted where the above entry will be reflected in SBP's annual accounts both on the asset (note 15) and liability side (note 25).

Note 15 shows that this is exactly where export refinance loans are recorded.

Taking HBL as an example, the ERF loan will be reflected in Asset (Note 9) and Liabilities (note 14).

HBL does not break down the advances by type of loans but provides a breakdown of borrowings. Hence, we can see how much has HBL has borrowed under ERF from SBP and can safely assume that the same amount has been lent out as Advances to exporters.

Aren't current account deposits a cheaper source of financing for HBL on account of being zero cost?

Firstly, commercial banks do not have unlimited current account deposits. More importantly, current account deposits present a higher liquidity risk than costly saving deposits. As the depositor isn't earning any income on the current account deposits, the depositor can withdraw the deposits at any time.

In contrast, refinancing from SBP may not be zero cost, but it is a better source as

It is significantly cheaper than all other sources of financing except current account deposits i.e. saving accounts or interbank borrowings and,

It is a stable source of financing i.e. it is for a fixed tenor i.e. 6 months to 10 years depending on the type of facility being used.

Thus the liquidity risk is all but eliminated in refinancings.

List of Refinancing Facilities of SBP

SBP provides refinancing for select loans against select collateral such as promissory notes and bills of exchanges. Below is the list of refinancing facilities offered by SBP along with the refinancing rate and the maximum spread allowed on those facilities.3

In addition to the above, there is the largest refinance facility i.e. ERF where the SBP refinance rate is 3% and commercial banks are allowed to charge a maximum spread of 2%.

As the cost of creating money for the central bank is zero, the central bank does not care what rate it charges on the refinance facilities. Whatever rate SBP charges, it is pure profit. This is the reason that SBP can afford to provide refinancing for hospitals i.e. RFCC at 0% as it does not cost SBP anything to create this money.

Why doesn't SBP create unlimited amounts of money as it doesn't face the same constraints as commercial banks?

Theoretically commercial banks can create unlimited deposits by making unlimited loans, however, they are constrained by

Funding

Liquidity risk

Credit risk

Prudential Regulations.

SBP on account of being a central bank has no such constraints. Can SBP create unlimited money through refinancing facilities? Yes and No. While SBP isn't constrained by the same issues as a commercial bank, it has two constraints

Demand from commercial banks/credit risk

As discussed earlier, while there is unlimited money available from SBP to refinance, SBP does not take the credit risk of the borrower. On the due date, the commercial banks are expected to repay the refinancing loan whether the borrower repays the commercial bank or not. SBP provides refinancing only when commercial banks request refinancing and commercial banks request refinancing when they feel comfortable enough to extend a loan to a borrower. If the banks don't feel that the borrower is a creditworthy risk, they will not extend a loan to the borrower nor request refinancing from SBP on his behalf.

SBP Act

SBP Act defines both the activities that SBP can engage in and the activities that SBP is prohibited from. Section 17 defined the mechanism under which SBP can provide refinance facilities. SBP can provide refinancing as long as it is in the manner defined in Section 17. However, under section 20 of the revised SBP amended act, SBP is prohibited from engaging in quasi-fiscal activities which refinancing activity clearly is.

Section 4 - Quasi Fiscal vs Fiscal

Below I give an example of two activities that have the same economic impact i.e., they provide subsidized loans but one is classified as fiscal activity and the other as QFA.

Fiscal Activity - Housing Finance Subsidy

SBP issued a circular on March 25, 2021, with respect to housing finance that there is Rs.36 billion available to subsidize interest rate charged to borrowers on housing finance.

The below table details the mark-up subsidy that will be provided to borrowers.

Let’s take the first line. The borrower will be charged 5% while the bank will book the income at KIBOR+700bps. Let's assume a mortgage of Rs.2 million and KIBOR of 7%. For the first month, the bank will book an interest income of Rs. 23,333 i.e. Rs.2 million x 14% (7% KIBOR + 700bps) / 12 months. The bank can only charge the customer Rs. 8,333 (i.e Rs.2 million x 5%/12 months). Thus, the borrower will be provided a subsidy of Rs.15,000 (Rs.23,333 - Rs.8,333) in the first month.

It hasn't been stated but the subsidy will continue till Rs.36 billion runs out. How many houses can this subsidy finance? If the KIBOR remains 7%, this Rs.36 billion can subsidize 26,145 houses for 10 years (if their loan is for 20 years) in Tier 0. If the KIBOR remains 9% throughout this period, this can finance 20,959 Tier 0 houses.

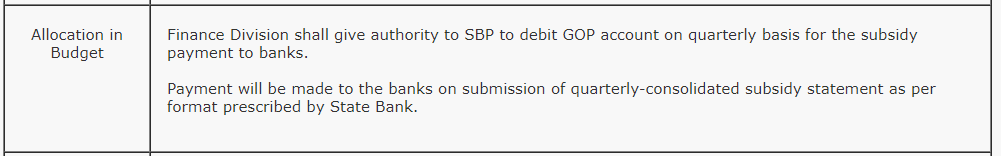

Who will pay this Rs.36 billion to the banks?

GoP will be making the payment. As per the SBP press release

Government of Pakistan has increased the total funding allocation to Rs36 billion on account of markup subsidy payment for financing over a period of 10 years and has assured continuity of the facility.

This Rs.36 billion would have been allocated and will be appearing in the budget of GoP 2021. Thus, when the federal government provides a subsidy, it is a fiscal activity and it appears in the budget of the government as a fiscal expense.

Needless to mention SBP can't even engage in this activity anymore as SBP is prohibited from development finance activities (DFAs) under the revised section 20 where DFAs are defined as "ANY ACTIVITY undertaken to promote any priority sector such as housing etc" as here SBP is promoting housing.

Next, we will see how quasi-fiscal activities are treated.

Quasi Fiscal Activity (QFA) vs Export Refinance (ERF)

ERF is the most prominent QFA of SBP, which is carried out under Section 17(a) of the SBP Act 1956 (as amended up to 2012). The way it works is an exporter approaches a commercial bank for a loan to manufacture an export order the borrower has received. The commercial bank approves an export loan to the borrower. On the same day, the commercial bank approaches SBP and SBP refinances (provides a loan to) the commercial bank by crediting the reserve account of the commercial bank maintained with SBP.

SBP charges commercial bank 3%. Commercial bank adds a spread of 2%. Thus the exporter ends up paying 5%. If this is a market rate transaction, the commercial bank would have lent money to the borrower at around 9%, a spread of at least 2% over KIBOR assuming the KIBOR is 7%. This means a subsidy of 4% is provided to the exporter (9% - 5% ERF rate).

For simplicity, let’s assume that on average Rs.400 billion of ERF was outstanding throughout the year. The total subsidy provided under ERF is at least Rs.16 billion in one year. But this subsidy is not appearing anywhere in the national accounts.

As the cost of funds for SBP is zero, SBP accounts will actually be showing interest income for charging the 3% ERF rate to the commercial banks.

Looking at note 34, SBP is only booking interest income from refinancing facilities provided to the financial institutions.

Thus while the economic impact of quasi-fiscal activities is similar to fiscal activities i.e. providing a subsidy to a sector, they do not appear as subsidies in the national budget rather appear as income in SBP books. This income is eventually paid to GoP as a dividend.

Ironic isn't it? Whereas fiscal subsidies appear as expenses in the government accounts, quasi-fiscal activities (despite being subsidies in nature) translate into income in government accounts when SBP pays dividends to GoP.

This may give you an inclination of why IMF and IMF trained SBP higher management is against quasi-fiscal operations. Based on various writings that I quickly skimmed, IMF dislikes quasi-fiscal operations as it distorts the budgetary picture and forces the central bank to take risks that it shouldn't. I should mention here that when it comes to export refinancing, RFCC or TERF, SBP does not take any risk. All the risk remains on the book of commercial banks. If the loan goes bad, the commercial banks are supposed to make good on the refinance to SBP on the maturity date and then pursue the borrower for recovery.

What about budgetary distortions? That is a valid point. Such distortions are acceptable sometimes. I covered earlier that by paying IPPs in PIBs, Abdul Hafeez Shaikh was understating Pakistan's budget deficit 2020/2021 by 0.2-0.3%. This understatement was apparently with the blessing of IMF.

The total amount (off-book expenditures as well as unpaid subsidies) that the news item is referring to are approximately Rs.165 billion. Thus as per the information available to date, the budget deficit for 2020/2021 will be understated by at least Rs.465 billion.

But this distortion by Abdul Hafeez Shaikh was a one-time event. When it comes to refinancings by SBP, the distortions become regular and a permanent feature. But it is easy to calculate the impact of refinancing as I just did above and make an adjustment in the government accounts if one so wishes.

Section 5 - The politics and optics of QFAs

When it comes to fiscal subsidies, the government has to arrange the resources for it, negotiate it with IMF, and get it approved in the budget from the parliament.

When it comes to quasi-fiscal subsidies, SBP has to just announce it by issuing the circular__ unelected technocrats wielding powers that the elected government ministers and even the prime minister can only dream of.

Deep in the throes of the Covid-19 crisis, these refinancings also provided SBP governor an opportunity to promote himself. No other central banker in the world has promoted himself as much as Reza Baqir during this crisis.

This was the banner on the SBP website on March 17 announcing the refinancing.

SBP tweeting on March 18 with Governor SBP video

On March 24, governor SBP releases another video relaxing the terms of the export refinancing scheme

On April 10, another banner with another refinancing scheme

On April 22, he even got an interview in Bloomberg as the most aggressive central banker in the world. The image is from the Bloomberg piece.

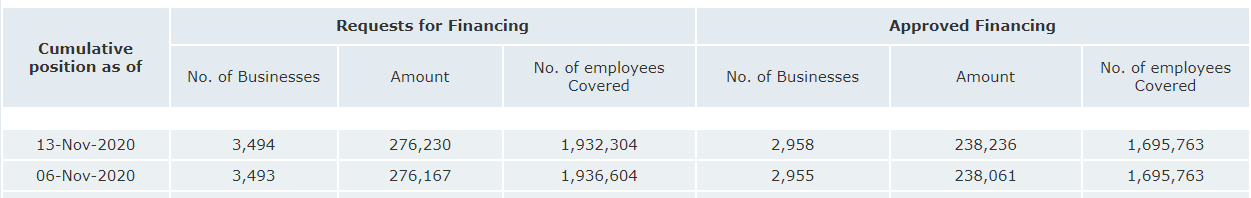

Rozgar refinancing scheme, as per the SBP website, covered the wages of 1.7 million employees.

It should be noted that SBP isn't taking any risk in any of the refinancing facilities. It is just creating free money and taking all the credit. The credit risk is on the books of commercial banks. If there is any risk-sharing, Federal Government is on the hook for it through fiscal measures.

Then there is TERF which provides a 10-year loan for setting up plant and industry. SBP charges only 1% and commercial banks can add a maximum spread of 4%. No other refinancing facility has been milked for SBP publicity as this one.

This was SBP governor last week

As many as 628 businesses have acquired concessionary bank loans amounting to Rs435.7 billion for setting up new businesses and/or expanding their existing production lines in Pakistan under the Temporary Economic Refinance Facility (TERF), which expired on March 31, 2021.

“Temporary Economic Refinance Facility (TERF) remained a highly successful scheme…this will push economic development and growth,” SBP Governor Reza Baqir said while speaking at the Pakistan Stock Exchange (PSX) on Monday.

“We told banks that we will hold them accountable through their asset quality indicators (like the ideas contribute to banks’ profitability or result in losses),” the governor said.

He added that the financing extended for expansion was equivalent to 1% of Pakistan’s gross domestic product (GDP).

How much free money did SBP create through these measures?

The central bank introduced several other concessionary financing schemes to support the economy, businesses and people during the pandemic.

“Total liquidity injected (through such schemes) over the last one year through a combination of all monetary measures...comes to around 5% of GDP (over Rs2 trillion),” he said.

Thus by engaging in these quasi-fiscal activities, SBP contributed at least 1% to the GDP of the country and created around Rs.2 trillion of free money (read liquidity) into the economy. Granted some of it is self-liquidating but we have seen with Export Refinance, it can easily become permanent financing (i.e. the money created is never extinguished as the loan balance keeps increasing). The federal government can only dream of injecting such liquidity without upsetting economists, IMF, budget deficit, and debt numbers.

It is unfathomable to me why SBP wants to give up such powers.

Section 6 - SBP Act: Much ado about nothing

It can take forever for the federal government or legislature to come up with such measures in times of crisis. The advantage of having such powers vested with central bank authorities is that it allows the central bank to quickly respond to the changing economic environment by creating money out of thin air. Plus when the federal government does it, it usually leads to brouhaha about favoritism, corruption and adds to the budget deficit.

If QFAs and DFAs are such productive activities, then why are they being prohibited. Reportedly it was inadvertent. If it is true, then it is highly unprofessional that a major piece of legislation that is going to the parliament is so poorly drafted.

We have already taken a similar regressive step earlier to comply with FATF in the Trust Act. Under the Punjab Trusts Act 2020, a company cannot be a trustee.

11. Who may be a trustee. − Every natural person capable of holding a property may be a trustee; but, where the trust involves the exercise of discretion, such person shall not execute it unless he is competent to contract under the Contract Act, 1872 _(IX of 1872)_.

**Explanation:** A legal person shall not be a trustee under this Act.

Similarly, I believe that this prohibition of QFAs and DFAs in the revised SBP act is intentional. If SBP wants to continue refinancing, SBP will have to either

Revise the language of Section 20 or

Add explicit carve-outs to allow refinancing or

Add a definition of QFAs that explicitly excludes refinancing activities from QFAs.

Most of the editorials and op-eds are focused on the independence of the central bank and the "security of tenure" of the SBP governor. A noble cause indeed. However, if people think that this amendment can provide security to the SBP governor, they are sadly mistaken. Just this month, the ordinance factory i.e. the president, was pleased to promulgate the amendment to the HEC Ordinance where he, with retrospective effect, reduced the tenure of HEC Chairman from 4 years to 2 years. Government can take a similar step with SBP governor if it so pleases.

The other major point of discussion has been that price stability should be the primary mandate of SBP. I have covered this earlier but this meme conveys it best

If I were to summarize the main points of the new amendment act, they'd be

Independence for SBP and SBP's governor. A noble cause indeed, but can be nullified with a single ordinance.

The misguided primary mandate of price stability which SBP has no capacity to achieve.

Prohibition of two of the most effective activities undertaken by SBP i.e. DFAs and QFAs.

At the end of the day, it is for the legislature to decide if they want unelected technocrats at SBP to wield so much power. SBP, for its part, does not want to do it. Once the legislation is passed, SBP will only be left with intervention in foreign currency markets and raising/dropping the discount rates to attract/repel hot money.

Conclusion

To summarize

SBP amendment act does not define QFAs.

As per IMF understanding, subsidized financing qualify as QFAs.

Refinance is nothing but a form of subsidized financing.

Refinancing is like a magic money tree. SBP can extend as much refinancing as required and it doesn't cost a penny to SBP for extending such facilities rather it translates into interest income for SBP that SBP can then pass on to the federal government as dividends.

Refinance activities allow SBP to quickly respond to a challenging economic environment.

SBP does not want to engage in QFAs. The amended act as it stands currently prohibits QFAs.

The discussions in the press have been about SBP's independence and primary mandate which as we have seen are a red herring.

Looking-Beyond-the-Budget-3-Quasi-Fiscal-Activities.pdf (internationalbudget.org) https://www.internationalbudget.org/wp-content/uploads/Looking-Beyond-the-Budget-3-Quasi-Fiscal-Activities.pdf

International Monetary Fund. Manual on Fiscal Transparency (esp. pp. 67-70). Washington, D.C.: International Monetary Fund. 2007. http://www.imf.org/external/np/pp/2007/eng/051507m.pdf

Financial Market Association of Pakistan](https://www.sbp.org.pk/Ecodata/sir.pdf