Monetary Policy 7 : SBP's misguided import compression?

SBP does not appreciate the side effects of its cash margin policy.

When SBP imposed a 100% cash margin on 114 items on September 30, 2021, it was justified in the following words

With economic growth having recovered and gaining momentum, SBP has decided to adjust its policy by imposing Cash Margin Requirement on additional 114 import items. This will complement SBP’s other policy measures to ease the pressure of import bill and help to contain the current account deficit at sustainable levels.

I wrote, what I like to think, a hard-hitting post titled “Fools in the shower” on what I believe were PR shenanigans by SBP as the items on the list comprised barely 2% of the import bill in 2019-2020. I found it hard to imagine how imposing 100% cash margin on such items can help reduce the import bill.

To summarize, SBP hopes to control current account deficit by imposing a 100% cash margin on items that comprise less than 2% of import bill. In terms of value, 25% of the items on the list comprise essential food items. Another 15% by value are such items as imported tiles, ceramics, kitchen electronics that would be a consequence of GoP’s construction amnesty and SBP’s push for construction financing and may not be affected by the cash margin at all as the end users are immune to such minor inconveniences as 100% cash margin. The rest is rubber, chemicals, paper etc. While dengue is prevalent, SBP feels that imposing a 100% cash margin on mosquito coils that comprise 0.02% of Pakistan’s import bill is beneficial.

On April 7, 2022, in tandem with issuing the Monetary Policy Statement, SBP issued another circular imposing a 100% cash margin on 177 import items in a bid to curb their imports.

In this regard, it has been decided that banks, with immediate effect, shall obtain 100 percent cash margin on the import of items as listed in the enclosed Annexure-A. The cash margins on these specific items will remain in place till December 31, 2022.

The cash margins deposited by importers on all items shall be non-remunerative.

In point 2 above, SBP is advising banks to not pay any interest on the 100% margin cash margin deposited with them by the importer. If the importer borrows money to deposit as margin — 3M Kibor is around 12%+ — and the LC is open for 6 months, this condition increases the cost of imported item by 6%.

I carried out the same exercise as I did in my earlier post and ran the SBP list of items through the PBS Imports by commodities and countries 2020-2021 report. The items on the SBP list add up to Rs.1.1 trillions of imports, almost 12.37% of the 2021 import bill. This is a larger proportion than the measly 2% of the September circular. Imposition of 100% cash margin this time may have slightly larger impact compared to the September 2021 list and may lead to import compression. [Caveat: The import data is till June 2021. The volumes may have changed since then].

In some categories SBP has tried to cover almost all the sub-categories, for example the first category of Boilers/machinery/part. There are 74 items in this category in the SBP list. For larger big ticket items or essential items, the importers won’t cancel such imports on a short notice, i.e., a machinery required for an under construction industrial plant will continue to be imported despite higher costs as otherwise the whole industrial plant will become a stranded asset. For essential items such as foodstuff or medicine, the importer will pass the cost of cash margin to the end users, thus adding to inflation. In the categories at the bottom, their import volume is so small that the 100% cash margin might deter their imports completely.

I will try to focus on the first 6 categories (above the dark line), as together they comprise 11.30% of the entire import bill. The rest of the categories collectively just make up 1% of the 2021 import bill.

The table below shows the largest import items in the Boilers/machinery/parts category and collectively comprise 3.27% out of the 3.82% of this category. Most of it is the industrial machinery, including textile machinery. I had thought Pakistan wants to embark on industrialization and increase exports. SBP’s 100% margin, if it deters the import of the below machinery, will have an opposite impact ie restric the import of very machines that are required for industrialization.

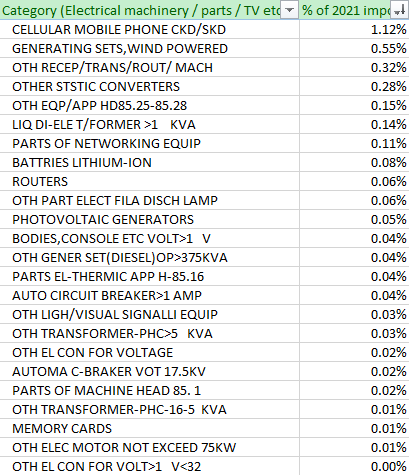

The next category is Electrical machinery. The biggest item in the category is the mobile phone Completely Knocked Down (CKD) kits and Semi Knocked Down (SKD) kits. Didn’t we just celebrate setting up mobile phone assembly plants locally? I do hope the industrialist who set up the plant wasn’t shocked by this margin. If the local assembled unit becomes expensive, it may lead to people opting for buying the imported units, as the difference in price may not be as large.

The next item in the category is wind powered generating sets. If we are moving towards renewable energy, it does not make sense to deter their imports. The rest of the items are again electrical and electronic items which don’t appear to be luxury items — such as I don’t know TV or DVD players, does anyone buy those anymore? — and common perception from reading the description is that these items help in the electrification of the country.

The next category is Iron and Steel. I can’t figure out from the description whether the below are industrial items or non-essential items. Someone who knows steel industry can comment on it. [If you are an expert, leave a comment and I will incorporate it here in my update].

The next item is food. No, no. Not luxury food. Staple food that a poor man needs to survive, such as peas and daal (gram dry whole). Beyond comprehension why SBP felt the need to impose a cash margin on daal.

BR Research had a great piece on daal last week and like me, they are flummoxed as to why SBP would try to compress demand of this staple food of the poor.

Pulses: keeping it steady - BR Research - Business Recorder (brecorder.com)

Given that daal chana (or gram) accounts for as much as 40 percent of total volume of pulses consumed locally, the relative stability in daal prices is of particular significance. Consider that over the past 10 years, Pakistan went from self-sufficiency in daal chana (gram) to importing at least 50 percent of annual demand.

Yet not only has the country not faced the specter of daal shortage, daal prices have risen much slower than prices of other staples such as flour or sugar; and in fact, at nearly the same pace as basmati rice, of which Pakistan exports a significant marketable surplus. All this, it bears emphasis, at a time when the currency has virtually been in a free-fall.

The answer to this mystery is of course a competitive import market. Pulses imports have so far been subject to little market intervention, with tens of small to medium sized trading firms fiercely competing with each other in a relatively low tariff environment.

Unfortunately, currency stability considerations have meant that the $0.75 billion annual import bill of pulses is now attracting growing scrutiny. Last week, SBP imposed cash margin requirement on pulses import, including gram dry whole – Pakistan’s favorite daal. Of course, SBP’s actions are driven by preference for demand suppression, without any due consideration to socio-economic concerns of affordability.

The bank can do precious little to increase local production in the short-term, while the likely increase in consumer prices as a result could mean smaller serving sizes for the poorest.

If I were to summarize what BR is saying in a political slogan, it would be

اسٹیٹ بنک نے غریب کے منہ سے دال کا نوالہ بھی چھین لیا

As if malnutrition isn’t already a problem in the country.

The next category is medicine and chemicals. The first two appear to be ingredients for the medicines, and the last one a chemical to add to beverages. Fine. We can’t afford to drink beverages. But why impose margin on medicinal ingredients? I am presuming those are medicinal ingredients as they are listed under that category. Last I heard, we are already facing shortage of medicines, as my good friend Motasim Bajwa keeps telling us about it.

Finally, we come to the pièce de résistance. The vehicle section. The country is importing too many luxury cars when it can’t afford to. If SBP is imposing a cash margin to deter imports of luxury cars, then it is a very good thing. Wait...What? The cash margin is not on luxury cars but on import of commercial vehicles such as trucks and tractors which are required for becoming part of value chain, connecting markets and increasing commerce. Oh, well.

Conclusion

Conclusion isn’t really needed after the above commentary, is it? While we can all agree that the current trade deficit is unsustainable and imports have to be compressed, using the 2021 data and SBP’s list, it appears that SBP is on the wrong path. It is deterring imports of items that lead to industrialization, electrification, and commercialization. While it is at it, it is also adding to malnutrition by making staple food expensive as well as exacerbating medicinal shortage.

What SBP needs to do is Smart Import Compression (I just added “smart” as it is the “in” word. I have no idea what smart import compression should be like 😀), which would require SBP to not just look at the proportion of the item in the import bill, but also see how deterring its import affects the well-being of the economy as well as the population.

NOTE: Please let me know in the comments if I got anything wrong, and I will rectify it. If you liked this post, press like and share it.